Stuck in a bowl in the Andes, as if in the bottom of an eggcup, Santiago's six million inhabitants are smothered under a thick smog pancake of their own creation. In contrast, Valparaiso, Chile's foremost port, has only three hundred thousand people, and it enjoys a cool Humboldt current breeze, blowing all one's exhaustion inshore and away.

In the same way that Los Angeles has expanded out onto ever more inhospitable and improbable patches of desert, Valparaiso has grown over the last century and a half to occupy every outrageous crag and outcrop of what once must have been seaside cliffs. Imagine repainting the architecture of New Orleans in a particularly acidic tropical palette, replanting it all on the most severe of San Franciscan topography, then squeezing it all together like an accordion, and you begin to grasp Valparaiso, where structures of all shapes and epochs clog the breath-stealingly steep cobblestone streets. As is the way in hill towns, no two facades seem to rest in quite the same plane, and from below the hills are a jumble of tilted surfaces of every imaginable hue.

Such buildings are best known to me from my travels in Haiti, and I was drawn to Waisberg's book after leafing through it and seeing numerous line drawings that one could easily imagine finding in the flesh in the streets of Port au Prince or Jacmel. It was only after buying it that I discovered in the back, in an appendix relating the international historical context of the Playa Ancha mansions, a line drawing of the Oloffson Hotel in Port au Prince. The setting for Graham Greene's novel The Comedians , it is one of the foremost remaining examples of Haiti's Victorian gingerbread architecture, on the terrace of which I have drunk innumerable punches and made innumerable friends. Perhaps it is these fond associations that account for this aberrant diversion from the modern in my architectural tastes.

, it is one of the foremost remaining examples of Haiti's Victorian gingerbread architecture, on the terrace of which I have drunk innumerable punches and made innumerable friends. Perhaps it is these fond associations that account for this aberrant diversion from the modern in my architectural tastes.

The "Olaffson" Hotel in Port au Prince as it appears in Casas de Playa Ancha. Another remarkable coincidence, as Waisberg only provides five drawings to illustrate the historical context of the Playa Ancha houses, three from Auckland, New Zealand, and two from Port au Prince. All illustrations taken from the book without any permission whatsoever. If you feel you are the legitimate owner of any pertinent copyrights and these reproductions are an issue for you, contact me through my profile.

The "Olaffson" Hotel in Port au Prince as it appears in Casas de Playa Ancha. Another remarkable coincidence, as Waisberg only provides five drawings to illustrate the historical context of the Playa Ancha houses, three from Auckland, New Zealand, and two from Port au Prince. All illustrations taken from the book without any permission whatsoever. If you feel you are the legitimate owner of any pertinent copyrights and these reproductions are an issue for you, contact me through my profile.Developed around 1900, with the bulk of buildings going up just after a devastating earthquake in 1906, Playa Ancha was planned out on a grid, but little sense of this structured layout is sensed by a wanderer of the streets. As Waisberg writes: "The intention of applying a plan based on the grid did not hold up to reality; it is generally difficult to perceive, thanks to topographic conditions characterized by profound channels cut by streams, and the accentuated disparity in the level of the land, which resulted in the persistence of historic trails that had followed the curve of the contours." (My translation). This turned out to be quite an understatement.

Despite being warned that I would be robbed, a favorite sport of Chileans (the warning, not the robbing), I wandered up to the once splendid neighborhood of Playa Ancha to track down a few of the spectacular buildings in Waisberg's thesis, which was first published almost 20 years ago. Those which I found are universally in need of your love, help and termite eradication skills. I did not carry a list of addresses with me, nor the book, lest I be mugged, but I am certain that some of the houses Waisberg studied have gone forever. Dotted amongst the mint, purple, ochre, lime and orange houses were ominous vacant lots and remnant mansions as badly in need of a fresh coat as any structure in Havana, where paint sometimes cannot be had for love or money. But the spectacular bones of many remain, awaiting plaster, power tools and teak oil. And a few hundred thou in plumbing. Those still standing are spectacular, but even if these rest were to crumble, their passing would do little to sully the glory of Valparaiso, whose charm rests in the constant collision of old and new, humble and grand, steep hill and sharp valley, painted and unpainted, water and land.

and teak oil. And a few hundred thou in plumbing. Those still standing are spectacular, but even if these rest were to crumble, their passing would do little to sully the glory of Valparaiso, whose charm rests in the constant collision of old and new, humble and grand, steep hill and sharp valley, painted and unpainted, water and land.

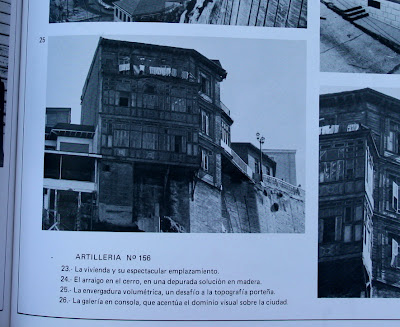

Artilleria #156 today; it is a restaurant hanging off the edge of the cliff

Artilleria #156 today; it is a restaurant hanging off the edge of the cliffWaisberg's photographs from 1988

A view of the same house from below, with the funicular-style public elevator that takes passengers to Playa Ancha

A view of the same house from below, with the funicular-style public elevator that takes passengers to Playa AnchaAbandoned by its middle class for jobs in the capital and the up-to-date horrors of nearby Viña del Mar, a Dubaiesque beachfront excrescence just along the coast, Valparaiso and its cable cars and public funicular elevators was left to the aged and infirm to wither and die with them. (Despite its brash hordes of loathsome high-rises jostling for ocean views, Viña del Mar remains Chile's most prestigious resort. When I told the locals of Easter Island, some of whom had never been to the South American continent, that I intended to visit Valparaiso they said "oh, no, don't go there, it's dingy and old, and you'll be robbed. Go to Viña, next door, it's much nicer.") Generations of university students have also temporarily lived in Valparaiso, writing on the walls before moving on, but despite the neglect the city is finally enjoying a sort of touristic rehabilitation, with, at least, Chileans visiting in droves. Here and there the occasional sushi bar or polished cafe has brought a touch of swank and income to the ground floor of one of the old houses, but the city is quite big enough to absorb a few mooks wandering the streets with maps and cameras without feeling as if it is turning into a museum. The occasional sea-captain in whites and braided cap is still to be found descending the endless cement staircases linking the hillsides with the port, and a stone's-throw from the docks in the petite flat market district dusty glass storefronts still display, without any irony whatsoever, hasps and coils of rope and fishhooks and oilskins and other marine frippery. There is little I could say in higher praise of a seaport town than this.

I'm looking at real estate. When the floods surge in the coming great melt, Valparaiso's container port may sink underwater, but my termite-ridden Victorian mansion will be high and dry. And painted fuschia, with eggplant trim.